How to Use Multifactor Funds for Smoother Returns

And Morningstar’s top-rated multifactor ETFs.

This article first appeared in the December issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of FundInvestor by visiting this website.

Factor investing is built on the premise that targeting specific characteristics of stocks can lead to market-beating returns. In 1993, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French developed the three-factor model. It introduced two new significant risk factors—small size and value—that explained stock returns in addition to market sensitivity, or beta. Since then, researchers have tested endless potential factors in their quest for excess returns.

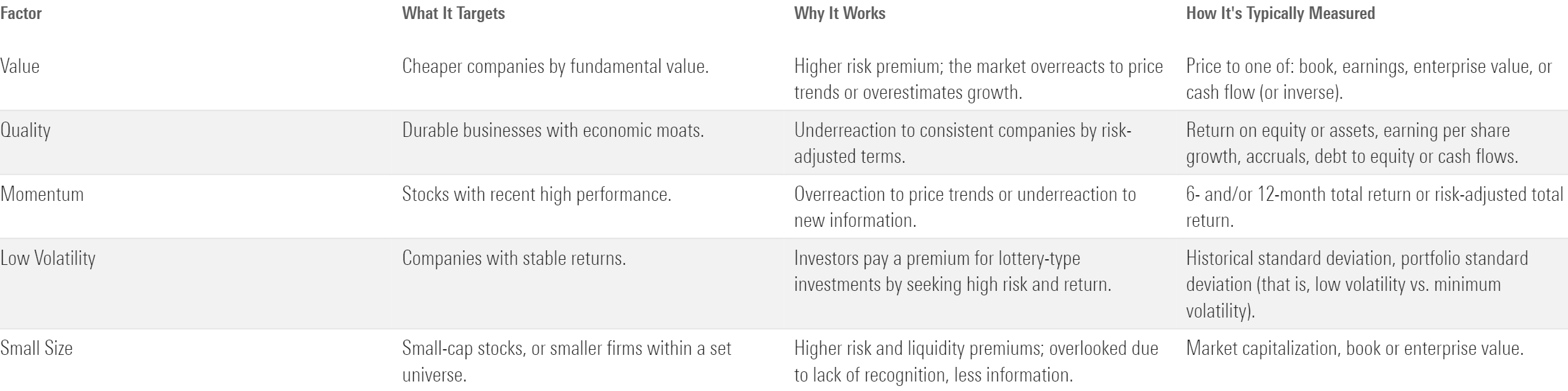

Subsequent empirical research has coalesced around five main risk factors: value, small size, quality, momentum, and low volatility. Exhibit 1 gives more details on the types of companies each factor targets, why each factor works—although this remains a great source of debate—and how funds typically measure them.

Focusing in on Each Factor

Academics and practitioners alike have vetted each of these five risk factors. On their own, they should provide a long-term advantage over the market. Investors have taken note, piling hundreds of billions of dollars into funds targeting these factors.

There is a catch to the long-term historical research underpinning these risk factors. The researchers had the benefit of looking at historical performance patterns over decades without fear of what the future held. In practice, the path to long-term excess returns can be rocky and trying for investors.

Greater volatility is one form of risk that accompanies some of these risk factors, and many come with behavioral risks. For example, investors who put all their eggs in the value basket have occasionally experienced long periods of underperformance. The same could be said for strategies that target the small-size, quality, and momentum factors. The low-volatility factor frequently runs into bouts of poor performance. Many low-volatility strategies were among the worst performers in 2020, failing to soften the market drawdown and then lagging the market on the rebound.

Investors may have a difficult time staying invested during stretches of underperformance. But diversification can often quell some risks, and the risks tied to these factors are no exception.

Enter multifactor funds. In theory, these funds target several risk factors that should lead to long-term excess returns while incurring less of the downside associated with any single factor. Diversified factor exposure means a given multifactor fund isn’t overly reliant on the relative performance of any one factor. The quality factor acts as ballast when value struggles, and low volatility picks up the slack when momentum drops off.

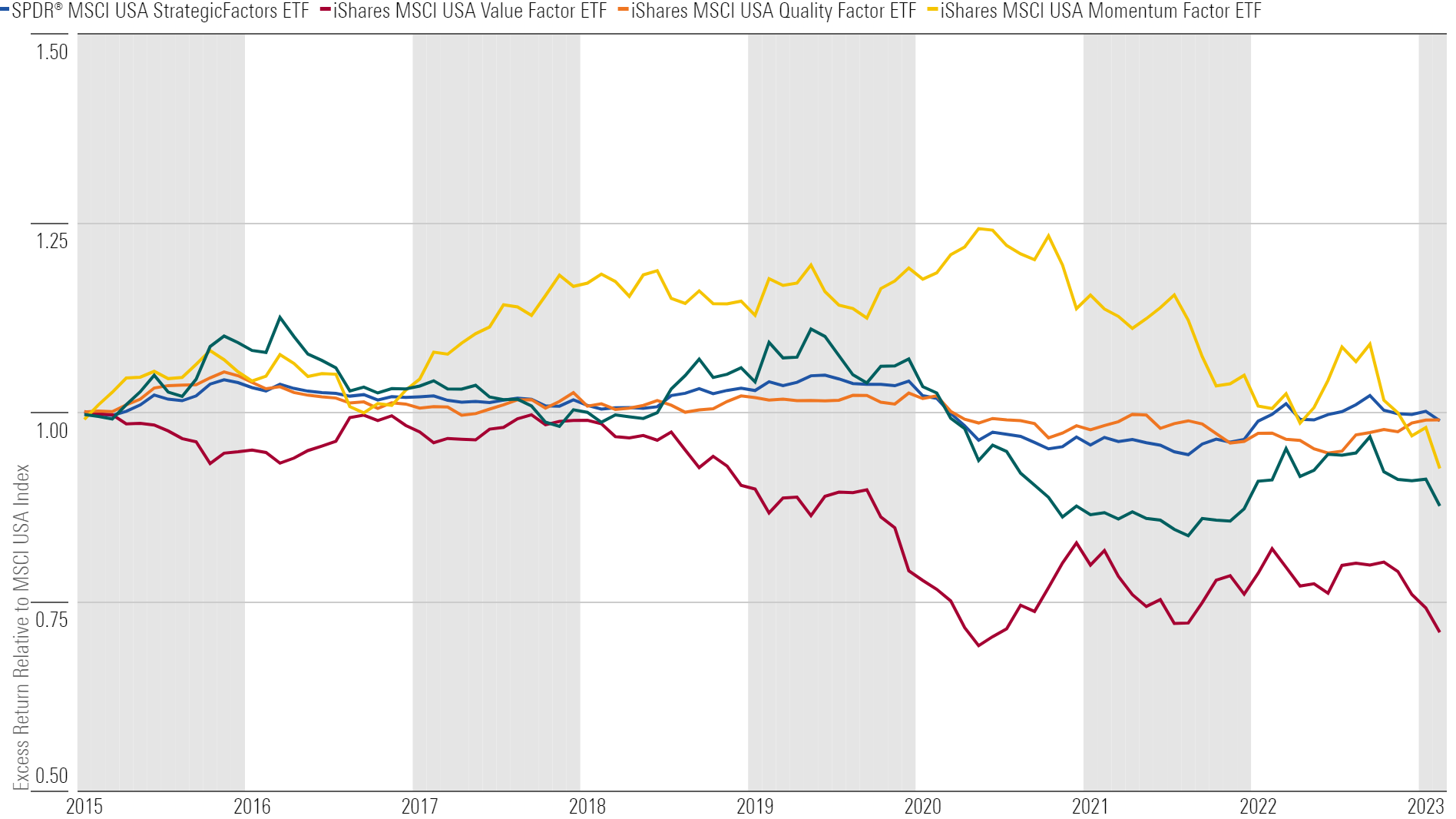

Exhibit 2 shows how multifactor funds can potentially smooth out returns, sometimes producing better results than their underlying individual factor funds. Each of these exchange-traded funds draws its holdings from the MSCI USA Index, with SPDR MSCI USA StrategicFactors ETF QUS combining value, quality, and minimum-volatility factor sleeves into one portfolio. Notably, QUS took the most consistent path toward excess returns, ultimately beating each of its underlying factors over the past eight years (starting at the latest inception date for these funds).

The Whole Can Be Greater Than the Sum of the Parts

The Many Faces of Multifactor Funds

Multifactor funds are built on the premise of targeting multiple factors while avoiding too much exposure to any single factor. But multifactor funds can target different combinations of factors, use different metrics to quantify factor exposure, and take different approaches to portfolio construction.

Value sits most prominently in multifactor funds’ factor exposure, with the median fund ranking in the top 27th percentile of funds by value. Multifactor funds tend to hold above-average exposures to small-size and momentum characteristics as well. Quality and low-volatility exposure tends to sit near the average fund, but the dispersion of low-volatility exposure is high.

Multifactor approaches can vary along several different dimensions. First, all funds don’t target the same set of factors, which is evident in the wide range of factor exposures. Some funds may intentionally exclude certain factors while focusing more closely on others. Value stands out as an exception: It tends to form the cornerstone of most multifactor portfolios.

Second, targeting multiple factor characteristics can dull exposure to individual factors. For example, profitable, high-quality firms and those trading at low price multiples likely don’t share many of the same fundamental traits. Combining quality and value stocks can therefore wash out strong exposure to both factors.

Third, factor exposure strength varies across a wide spectrum of approaches. Some funds take a market-cap-weighted portfolio and add minor tilts toward factor exposures. Others home in on a select set of names that exhibit the strongest factor characteristics.

This leaves investors with a few options. The first two considerations require a trade-off: A fund’s diversification comes at the expense of more-potent factor exposure. In some cases, this may improve a multifactor fund’s returns. A quality screen for a value fund can help it avoid value traps without completely diminishing the factor exposure.

The third consideration raises another trade-off: More-concentrated portfolios with higher factor exposures also come with a higher degree of active risk. Given the long-term efficacy of factor exposures, should investors take on more active risk to increase factor exposures in multifactor funds?

The Costs of Active Risk

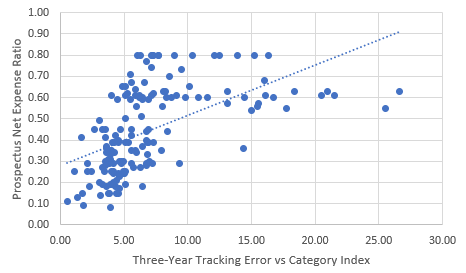

This analysis of multifactor funds leads us back to the familiar territory of managing risks and costs. Maximizing factor exposure may seem like the optimal choice. But more-concentrated portfolios introduce more stock-specific risks, and they tend to come with higher price tags. Exhibit 3 charts a comparison of multifactor funds’ fees and their three-year tracking error against their category index as a proxy for active risk.

Active Risk Comes With A Higher Price Tag

Multifactor funds with fees below 25 basis points almost exclusively come with tracking error below 5%. Higher tracking error often translates to higher expense ratios. Fees are among the best predictors of success, giving high-active-risk strategies a gloomy outlook.

A Free Lunch

Diversification is the only free lunch in investing, as Harry Markowitz would say. Multifactor funds balance multiple factor exposures in one portfolio, benefiting from each in the long run while avoiding long droughts customary to single factors. This helps smooth returns and improve investor confidence to stay invested and avoid selling at the bottom.

But diversification doesn’t stop with factor exposures. Concentrated portfolios open the door for uncompensated risks, like stock-specific risks or sector biases. The best option for the long haul remains a sensible, broadly diversified strategy. Marrying this with diversified factor tilts should provide investors with the best chance of success.

Our Favorite Multifactor ETFs

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OD5MWLUGVNACNGNQH5RHWD56MQ.png)